आरोग्य समाचार

(१)एक प्याला कॉफी का रोज़ाना सेवन गिरती बीनाई (विजन ,vision

,नज़र )को थाम सकता है अलावा इसके ग्लूकोमा ,बढ़ती उम्र तथा

मधुमेह से पैदा होने वाले रेटिना विकृति (रेटिनल डिग्रेडेशन )को भी

मुल्तवी रखने में सहायक हो सकता है।

Raw coffee contains 7to 9 % chlorogenic acid (CLA ),a strong

antioxidant that prevented retinal degeneration (रेटिना का

अपविकास ,रेटिना का छीज़ना रोक सकता है कॉफी में मौजूद

क्लोरोजीनिक एसिड )

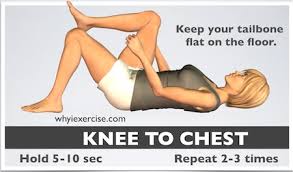

(२) स्ट्रेचिंग व्यायाम पेशीय लोच को बढ़ाते हैं ,चोट लगने पेशी

के क्षतिग्रस्त होने की संभावना को कमतर करते हैं

(१)एक प्याला कॉफी का रोज़ाना सेवन गिरती बीनाई (विजन ,vision

,नज़र )को थाम सकता है अलावा इसके ग्लूकोमा ,बढ़ती उम्र तथा

मधुमेह से पैदा होने वाले रेटिना विकृति (रेटिनल डिग्रेडेशन )को भी

मुल्तवी रखने में सहायक हो सकता है।

Raw coffee contains 7to 9 % chlorogenic acid (CLA ),a strong

antioxidant that prevented retinal degeneration (रेटिना का

अपविकास ,रेटिना का छीज़ना रोक सकता है कॉफी में मौजूद

क्लोरोजीनिक एसिड )

(२) स्ट्रेचिंग व्यायाम पेशीय लोच को बढ़ाते हैं ,चोट लगने पेशी

के क्षतिग्रस्त होने की संभावना को कमतर करते हैं

(3)Pill to switch off hunger on the horizon

LONDON: The world's first pill to make you stop eating is set to become a reality.

In a study led by Imperial College London and the Medical Research Council (MRC), an international team of researchers identified an anti-appetite molecule called acetate that is naturally released when we digest fibre in the gut. Once released, the acetate is transported to the brain where it produces a signal to tell us to stop eating.

The research confirms the natural benefits of increasing the amount of fibre in our diets to control overeating and could also help develop methods to reduce appetite.

The study found that acetate reduces appetite when directly applied into the bloodstream, the colon or the brain.

Dietary fibre is found in most plants and vegetables but tends to be at low levels in processed food. When fibre is digested by bacteria in our colon, it ferments and releases large amounts of acetate as a waste product. The study tracked the pathway of acetate from the colon to the brain and identified some of the mechanisms that enable it to influence appetite. This is the first demonstration that acetate released from dietary fibre can affect the appetite response in the brain.

Using positron emission tomography (PET) scans, the researchers tracked the acetate through the body from the colon to the liver and the heart and showed it eventually ended up in the hypothalamus region of the brain, which controls hunger.

"The average diet in Europe today contains about 15 g of fibre per day," said lead author of the study Professor Gary Frost from Imperial College London. "In stone-age times we ate about 100g per day but now we favour low-fibre ready-made meals over vegetables, pulses and other sources of fibre. Unfortunately our digestive system has not yet evolved to deal with this modern diet and this mismatch contributes to the current obesity epidemic. Our research has shown that the release of acetate is central to how fibre suppresses our appetite and this could help scientists to tackle overeating."

The study analyzed the effects of a form of dietary fibre called inulin that comes from chicory and sugar beets and is also added to cereal bars. Using a mouse model, researchers demonstrated that mice fed on a high fat diet with added inulin ate less and gained less weight than mice fed on a high fat diet with no inulin. Further analysis showed the mice fed on a diet containing inulin had a high level of acetate in their guts.

"The major challenge is to develop an approach that will deliver the amount of acetate needed to suppress appetite but in a form that is acceptable and safe for humans," Professor Frost said. "Acetate is only active for a short amount of time in the body so if we focused on a purely acetate-based product we would need to find a way to drip-feed it and mimic its slow release in the gut."

Professor David Lomas from MRC said: "It's becoming increasingly clear that the interaction between the gut and the brain plays a key role in controlling how much food we eat. Being able to influence this relationship, for example using acetate to suppress appetite, may in future lead to new, non-surgical treatments for obesity."

LONDON: The world's first pill to make you stop eating is set to become a reality.

In a study led by Imperial College London and the Medical Research Council (MRC), an international team of researchers identified an anti-appetite molecule called acetate that is naturally released when we digest fibre in the gut. Once released, the acetate is transported to the brain where it produces a signal to tell us to stop eating.

The research confirms the natural benefits of increasing the amount of fibre in our diets to control overeating and could also help develop methods to reduce appetite.

The study found that acetate reduces appetite when directly applied into the bloodstream, the colon or the brain.

Dietary fibre is found in most plants and vegetables but tends to be at low levels in processed food. When fibre is digested by bacteria in our colon, it ferments and releases large amounts of acetate as a waste product. The study tracked the pathway of acetate from the colon to the brain and identified some of the mechanisms that enable it to influence appetite. This is the first demonstration that acetate released from dietary fibre can affect the appetite response in the brain.

Using positron emission tomography (PET) scans, the researchers tracked the acetate through the body from the colon to the liver and the heart and showed it eventually ended up in the hypothalamus region of the brain, which controls hunger.

"The average diet in Europe today contains about 15 g of fibre per day," said lead author of the study Professor Gary Frost from Imperial College London. "In stone-age times we ate about 100g per day but now we favour low-fibre ready-made meals over vegetables, pulses and other sources of fibre. Unfortunately our digestive system has not yet evolved to deal with this modern diet and this mismatch contributes to the current obesity epidemic. Our research has shown that the release of acetate is central to how fibre suppresses our appetite and this could help scientists to tackle overeating."

The study analyzed the effects of a form of dietary fibre called inulin that comes from chicory and sugar beets and is also added to cereal bars. Using a mouse model, researchers demonstrated that mice fed on a high fat diet with added inulin ate less and gained less weight than mice fed on a high fat diet with no inulin. Further analysis showed the mice fed on a diet containing inulin had a high level of acetate in their guts.

"The major challenge is to develop an approach that will deliver the amount of acetate needed to suppress appetite but in a form that is acceptable and safe for humans," Professor Frost said. "Acetate is only active for a short amount of time in the body so if we focused on a purely acetate-based product we would need to find a way to drip-feed it and mimic its slow release in the gut."

Professor David Lomas from MRC said: "It's becoming increasingly clear that the interaction between the gut and the brain plays a key role in controlling how much food we eat. Being able to influence this relationship, for example using acetate to suppress appetite, may in future lead to new, non-surgical treatments for obesity."

In a study led by Imperial College London and the Medical Research Council (MRC), an international team of researchers identified an anti-appetite molecule called acetate that is naturally released when we digest fibre in the gut. Once released, the acetate is transported to the brain where it produces a signal to tell us to stop eating.

The research confirms the natural benefits of increasing the amount of fibre in our diets to control overeating and could also help develop methods to reduce appetite.

The study found that acetate reduces appetite when directly applied into the bloodstream, the colon or the brain.

Dietary fibre is found in most plants and vegetables but tends to be at low levels in processed food. When fibre is digested by bacteria in our colon, it ferments and releases large amounts of acetate as a waste product. The study tracked the pathway of acetate from the colon to the brain and identified some of the mechanisms that enable it to influence appetite. This is the first demonstration that acetate released from dietary fibre can affect the appetite response in the brain.

Using positron emission tomography (PET) scans, the researchers tracked the acetate through the body from the colon to the liver and the heart and showed it eventually ended up in the hypothalamus region of the brain, which controls hunger.

"The average diet in Europe today contains about 15 g of fibre per day," said lead author of the study Professor Gary Frost from Imperial College London. "In stone-age times we ate about 100g per day but now we favour low-fibre ready-made meals over vegetables, pulses and other sources of fibre. Unfortunately our digestive system has not yet evolved to deal with this modern diet and this mismatch contributes to the current obesity epidemic. Our research has shown that the release of acetate is central to how fibre suppresses our appetite and this could help scientists to tackle overeating."

The study analyzed the effects of a form of dietary fibre called inulin that comes from chicory and sugar beets and is also added to cereal bars. Using a mouse model, researchers demonstrated that mice fed on a high fat diet with added inulin ate less and gained less weight than mice fed on a high fat diet with no inulin. Further analysis showed the mice fed on a diet containing inulin had a high level of acetate in their guts.

"The major challenge is to develop an approach that will deliver the amount of acetate needed to suppress appetite but in a form that is acceptable and safe for humans," Professor Frost said. "Acetate is only active for a short amount of time in the body so if we focused on a purely acetate-based product we would need to find a way to drip-feed it and mimic its slow release in the gut."

Professor David Lomas from MRC said: "It's becoming increasingly clear that the interaction between the gut and the brain plays a key role in controlling how much food we eat. Being able to influence this relationship, for example using acetate to suppress appetite, may in future lead to new, non-surgical treatments for obesity."

Pill to switch off hunger possible as 'anti-appetite' molecule discovered

Dieters could soon benefit from a pill that switches off hunger after scientist found that fibre reacts with the gut to produce an 'anti-appetite' molecule

कमसे कम खुराक में ४० % जगह फल और

तरकारियों को दीजिये क्योंकि इनसे प्राप्त

खाद्यरेशे अंतड़ियों में एसीटेट निसृत (मुक्त

करना ,छोड़ना )करते हैं जिससे निकट भविष्य में

एक ऐसी टिकिया (खाने की गोली )तैयार की जा

सकेगी जो आपको पेटू होने ओवर ईट करने से

रोक देगी। आपको पेट भर जाने का एहसास कम

खाने के बाद हो करवा देगी

A pill that switches off hunger is on the horizon after scientists discovered an ‘anti-appetite’ molecule which tells the body to stop eating.

Researchers at Imperial College discovered that people feel full when eating fruit and vegetables because fibre releases acetate into the gut.

They believe that a pill derived from acetate could be created to help people cut down on food without experiencing any cravings.

One in four adults in England is obese and that figure is set to climb to 60 per cent of men and 50 per cent of women by 2050.

Obesity and diabetes already costs the UK over £5billion every year which is likely to rise to £50 billion in the next 36 years.

A pill which switches off hunger could be developed by scientists Photo: Alamy

कोई टिप्पणी नहीं:

एक टिप्पणी भेजें